The Tragic 2019 Fire at Notre Dame Cathedral

[This blog post is the second in a two-part series. Read the first blog, "How Mature is the Federal Government’s Practice of Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) now that the OMB Circular A-123 Update is Turning Five?"]

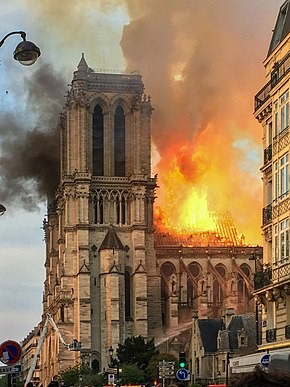

It was a beautiful spring day in Paris on April 15th, 2019 when tourists walking about the Île de la Cité in the early evening noticed something unusual at Notre-Dame – smoke was wafting above the Cathedral. Word began to spread quickly, and as the gaze of bystanders was drawn to the iconic spire of the landmark, one tourist tweeted at 6:52 p.m., “It appears Notre-Dame is on fire.”[i]

Almost 35 minutes before this tweet, at 6:18 p.m., an alarm sounded in the cathedral, notifying a security employee that smoke was detected. Scanning an electronic panel that relayed information about the alarm, the employee radioed a guard and asked him to check the attic for smoke or fire. The guard ran to the attic of the sacristy, a small annex to the side of the cathedral, did not see any signs of fire, and radioed “all-clear” to the security employee.

At 6:28 p.m., the security employee, who started in the position two days prior and was working a double shift after his replacement failed to show, called his manager to tell him about the alarm, but the manager did not pick up. At 6:33 p.m. the manager returned the employee’s call and in discussing what happened, determined that the guard had gone to the wrong place to check for fire. He told the security employee to have the guard run to the attic of the main cathedral. A second alarm sounded at 6:43 p.m. At 6:48 p.m., the guard discovered the fire burning out of control. He radioed the security employee to call the fire department. More than 30 minutes since the first alarm sounded, the fire department was finally notified.

Notre-Dame was undergoing renovations, and scaffolding was erected above the roof and around the spire. Either an electrical spark from a construction elevator or a discarded cigarette (investigators still don’t know for sure which one was the cause) started smoldering and quickly turned into an inferno that almost, but for the brave heroics of the Paris fire brigade, consumed the entirety of this historic edifice.

Notre Dame Cathedral had an elaborate fire protection plan that a team of experts spent six years and untold funds to develop. The plan involved thousands of pages of diagrams, maps, spreadsheets, and contracts[ii]. Drills were run to test the plan, yet when the system was put to a real test, it failed in spectacular fashion before a world-wide audience. A look into some of the assumptions, factors and components that went into creating the protection plan provides some important lessons that can be applied to the practice of risk management.

Risk is the possibility that an event will occur and affect the achievement of strategy and business objectives. Organizations, programs, projects and initiatives may have competing objectives, where pursuing one objective can cause risks for another. The team of historical preservationists that developed the plan for Notre-Dame were charged with two primary objectives: protect the historical integrity of the structure and protect the building and visitors from threats such as fire. These two objectives, while seemingly similar in intent, created potential conflict when decisions were being made about the type and extent of fire detection and prevention systems to install.

Risk appetite is the type and amount of risk, on a broad level, an organization is willing to accept in pursuit of its objectives. Decisions to install modern safety equipment and procedures were subsequently weighed against the impact such measures would have on the structure, in particular, the wooden attic, which was built with the oak from hundreds of trees harvested in the 12th and 13th centuries. Often referred to as “the forest,” it was hidden away from public view behind the cathedral’s soaring vaulted stone ceiling. The team of historical preservationists had a low risk appetite for anything that might compromise the historical integrity of the forest.

Had there been a bit more diversity in the make-up of this team to bring in alternative viewpoints beyond just those of preservationists, it’s possible the appetite for risk might have been different. But, after weighing the risks to both objectives and considering the likelihood and impact of the potential risks, such as a fire, the team of preservationists decided not to erect firewalls or add sprinklers to the attic. As it was, the cathedral stood strong for 850 years, making it through the French Revolution and two world wars. If a fire were to occur, they thought it could be quickly detected and then contained.

The assumption that if a fire ever started in the attic at Notre-Dame there would be plenty of time to do something about it was based on a belief held by the former chief architect of the fire protection plan. He believed that the ancient oak timbers, because of their density and thickness, would burn slowly, thereby allowing time for flames to be put out before spreading[iii]. However, according to fire safety experts, calculating the time it takes a fire to burn through heavy timber is much different than calculating how quickly a fire will spread across the timbers. These experts noted that, once lit, a fire in a heavy timber structure would spread extremely quickly and be difficult to extinguish.

It’s uncertain whether this underlying assumption was ever tested or validated, or whether any other members of the team felt comfortable questioning the chief architect’s belief. But given how critical and crucial this key assumption was to everything else that followed in the development of the fire protection plan, further time and effort likely should have been spent in weighing and evaluating this assumption.

If the risk velocity was rated as high, the protection plan more likely would have emphasized quick detection and rapid action. The plan at Notre Dame however, shaped by the assumption that there would be sufficient time if a fire was detected to put it out before it grew beyond control, allowed for built-in delays.

In addition to manual alarms placed throughout the cathedral, an elaborate and sophisticated smoke detection system of tiny tubes with airholes was ultimately installed. These aspirating detectors checked for smoke, and, when detected, an alarm sounded. With more than 160 detectors located throughout the vast cathedral, a messaging system was developed to tell a security employee monitoring the system where an alarm went off. The code identified which of four zones in the cathedral the detector was located, which specific detector sounded, and what type of detector it was. On the job only three days, it’s unclear whether the security employee properly deciphered the coded message.

After the alarm sounded, a cathedral guard was required to first confirm that a fire was burning before the fire department was notified. This was standard practice in Paris, with some exceptions, such as the Louvre, which had its own on-site fire brigade. By not notifying the fire department as soon as the alarm sounded at Notre-Dame, valuable time was lost. Given the historical and cultural significance of Notre-Dame, it seems an exception should have been made for the cathedral, but such a request was apparently never considered.

Because of the decision not to install video cameras and the accompanying electrical wiring in the attic, when an alarm sounded there, a guard needed to climb 300 steps up a set of steep and winding stairs – a trip that would take a fit person several minutes. By the time this was done, and if a fire was found – it would take another twenty minutes or more before the fire department would arrive and climb to the attic to begin battling the fire. Those delays turned out to be devastating.

As we know, the guard first ran to the wrong place. After finding no signs of fire in the attic of the sacristy, the guard gave the all-clear, leading the security employee to surmise that the alarm system must have malfunctioned. However, neither the guard nor the security employee set about immediately to investigate if and why the alarm was malfunctioning, hence losing valuable time. Only after the call with the manager, who was able to decipher the mistake, was the guard sent to the correct location where he found the attic ablaze.

Nearly an hour after the first alarm sounded, the Paris Fire brigade arrived. At 7:50 p.m., the roof and the spire collapsed, punching holes into the ceiling of Notre-Dame and raining fire and debris down on the cathedral floor. To save the structure from further collapse, the firefighters focused their efforts on saving the twin towers. They bravely worked throughout the night pumping water from the Seine through hoses lugged up the narrow and steep stairs. By 4 a.m. the next morning, the fire was finally under control. Notre-Dame was saved, but just barely. (You can watch the one-hour riveting documentary, The Battle for Notre Dame, to find out how close the cathedral came to collapse). With embers still glowing, French President Macron declared that the cathedral would be rebuilt and ready to receive visitors by the time France hosts the 2024 summer Olympics.

Questions for Risk Management Practitioners to Consider

- What is your organization’s most valued asset, its Notre-Dame so to speak?

- What assumptions underpin your risk response strategy, and were those assumptions tested and vetted? Have alternative points of view been considered? Or sought out?

- Do you have competing objectives that your risk response plan seeks to protect? If so, how have you weighed the likelihood, impact, and, perhaps most critically, the velocity of risks to those objectives?

- What is the risk appetite of those who developed the risk management plan? Are the risks they accepted in-line with the level of risk that leadership is willing to take? Should others have been involved or consulted?

- Are there any components of your risk response strategy or risk management plan that are based on the status quo, where established policies and procedures were accepted as is, without effort to determine if alternatives or new approaches were necessary?

- Are your key risk indicators clear, actionable, and easy to understand?

- When a risk threshold is passed or a triggering event occurs, are there any critical dependencies that must then be in place for the risk alert message to get through? If so, have you sought out ways to simplify or remove those dependencies?

- Is your risk response plan overengineered? Does the plan allow for quick action?

- How thorough are your processes for evaluating and investigating risks? Are they easily dismissed or is there a method in place to ensure they receive adequate consideration and attention?

- How often do you review and update your risk response strategy? Are there any triggering events that mandate an update to the strategy? If not, should there be?

Epilogue

The COVID-19 pandemic slowed down work to stabilize the cathedral and begin renovations, but in the summer of 2020, French government officials decided to restore the roof and the spire back as they were before the fire, and a team was formed to scout the countryside for another forest of trees whose wood will be cut and brought to Notre-Dame. When that wood is hewn and finally lifted into place, it will made as historically accurate as possible – albeit with two exceptions – sprinklers and cameras are expected to take their place among the oak rafters.

To follow the reconstruction progress, and/or to make a contribution toward the rebuilding of Notre-Dame Cathedral, visit the website of the Friends of Notre-Dame de Paris, a 501(c)(3) public charity.

About the Author

Tom Brandt is Chief Risk Officer for the Internal Revenue Service. He previously lived and worked in Paris and was a frequent visitor to Notre-Dame. In reading and learning about the fire and the protection plan that ended up failing to protect the cathedral as intended, Tom identified a number of important lessons that could be applied to the practice of risk management which he first shared in a webinar and podcast on April 15, 2020. This article summarizes and offers key highlights from that podcast.

[i] Peltier, Elian; Glanz, James; Grondahl, Mika; Cai, Weiyl; Nossiter, Adam; Alderman, Liz; “Notre-Dame came far closer to collapsing than people knew. This is how it was saved.” New York Times, July 18, 2019

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Benhold, Katrin and Glanz, James; “Notre-Dame’s Safety Planners Underestimated the Risk, with Devastating Results,” New York Times, April 19, 2019.

Photo credits: Wikipedia