Acquisition Reform in the 1990s: Lessons from a By-Gone Era for Today

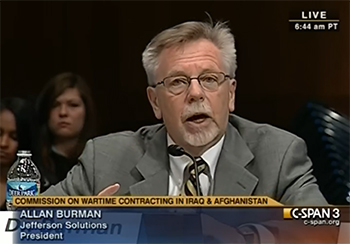

This guest post by Allan Burman, President of Jefferson Solutions and former Administrator, Office of Federal Procurement Policy in the Office of Management and Budget, is part of a longer series on government reforms over the past 30 years and lessons for future leaders.

Attention to government procurement and acquisition has long been a focus of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and Congress. As Administrator of the Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP) OMB from 1988-1993, I often spoke about procurement issues and reforms before congressional committees.

Back then, if I were going to the Hill to testify (and I did this over 40 times as the OFPP Administrator) the scene was generally the same. Most of my hearings would be before what was then the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee or the House Government Operations Committee. The process would often play out as follows: a witness from the General Accounting Office would testify first, recounting in deep detail the inadequacies of procurement staff or an agency in carrying out its acquisition responsibilities. And then I would be asked to explain the reasons for this failure and what I was going to do about it.

Acquisition Reform in the 1990s: Then and Now with Allan Burman, former Administrator, Office of Federal Procurement Policy, OMB.

What seems so different from today though was how uniformly the situation involved a bipartisan raking over the coals of Administration witnesses. Democrat and Republican members of Congress seemed to look to outdo each other in making their complaints. In particular I recall many sessions before Senator Carl Levin, Democrat from Michigan, and Senator William Cohen, Senator from Maine (I used to call these “opportunities to excel”) who regularly had Administration witnesses, me included, on the ropes. Both were always well prepared for the hearings and knew where they were going. And woe to you if you weren’t and didn’t.

A few tips for budding witnesses:

- You don’t ask the questions, you’re there to answer them. Senator Levin very clearly made that point to me when early on in one hearing I asked him to address a concern about something he was asking;

- As much as you hate to reveal to the world you are not knowledgeable on some aspect of your job, if you don’t know the answer to a question, don’t make something up. You’ll get caught and that’s not pretty. It’s always better to say I’ll get back to you on that. And,

- Look through the Washington Post and the New York Times the day of the hearing because frequently there will be something in there that may somehow relate to your field (however remotely) and, if so, you may well get a question on it.

I had been acting Administrator since May1988, receiving my Senate confirmation in March 1990 under President George H. W. Bush. OFPP had been set up in the 1970s as a part of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Its charge was to respond to a litany of complaints from Congress and others on, among other things, the mass of inconsistent rules and regulations affecting the procurement process as well as how long it took to buy things. I was the sixth person to have held the post. Mike Wooten today is number 15.

Legislation from Then, Still Important Today. When I became acting Administrator in the late 1980s, there were not only concerns about inefficiencies but also complaints about widespread corruption. Both of these issues had a significant effect not only on my areas of focus as Administrator but ultimately on major pieces of legislation still affecting the acquisition process today. One was the Procurement Integrity Act of 1988 and the other was the Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act of 1994.

Congress passed the Procurement Integrity Act as a way to prevent the abuses disclosed in a three year-investigation by the FBI called Operation Ill Wind. This investigation resulted in some 50 government officials, consultants and military contractors being convicted of various crimes including bribery and conspiracy to defraud the government. Some contractors obtained proprietary and sensitive procurement information that would give them a major advantage in any procurement. Representative Jack Brooks’ House Government Operations Committee and Senator John Glenn’s Senate Governmental Affairs Committee had fashioned legislation called the Procurement Integrity Act to offer a series of constraints on inappropriately obtaining such information, including adding criminal penalties for non-compliance. The law also prevented contracting officials for procurements over $10 million for one year from going to work for a contractor receiving the award.

While the legislation directly addressed the Ill Wind concerns, it also added a new level of uncertainty for both government and contractor personnel on what constituted the information not to be obtained. In fact, a small cottage industry sprang up in creating little cards to remind people about the do’s and don’ts of asking for or releasing such information. For a naturally risk-averse community, you can imagine the effect this had on the general level of communication between government and industry. So, this legislation set in motion one element of the 1996 Federal Acquisition Reform Act that made it clear that the procurement integrity legislation never intended to shut down such communication.

Reform Efforts Then, Mirrored Today. I have recently completed my service as a Commissioner of the Section 809 Panel, another effort by Congress to simplify and speed up Defense procurement. Our January 2019 report includes a bundle of recommendation reinforcing the importance of better communications between government and industry to get quality and speed in procurements. It also proposes a new streamlined approach for purchasing readily available products and services.

The charter for the original Section 800 Panel, based on Section 800 of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for FY1991, served as a basis for that of Section 809 of the FY 2016 NDAA. I was one of thirteen members of government and industry to serve on that earlier panel. Streamlining and codifying acquisition laws were the tasks, but with speed and commercial buying major goals for the panelists. Initially the focus was to be government-wide, but with Hill Committees not coming to agreement on an approach, it’s focus shifted to Defense. The House Government Operations Committee staff had concerns about my participation, since I wouldn’t be chairing it and it had a narrower focus. My view was so many of the reforms would likely have government-wide impact, and I didn’t want to see civilian agencies lose out on the benefits, so I accepted the invitation to serve on it.

The Section 800 Panel met regularly down at Fort Belvoir on a monthly basis for a couple of years, with Rear Admiral Bill Vincent, the head of the Defense Systems Management College, serving as an excellent Chair. George Washington University Professor Ralph Nash with his terrific background in contracting was one of my fellow panelists as was the Air Force’s Head of Contracting, Major General John Slinkard, who was always generous to me with his time and advice. And what we produced was ultimately incorporated into the Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act of 1994 or FASA with its easy-to-use $2500 micro-purchase threshold, its simplified processes for procurements under $100,000 and perhaps, most importantly, its commercial item procurement language that has stood the test of some 25 years.

Imagine procurement having the level of importance that would bring a unanimous bipartisan Congress together in support of a stand-alone bill fixing how the government does its business. That would be a true Federal government success story!