Evolution of Performance Management in Government

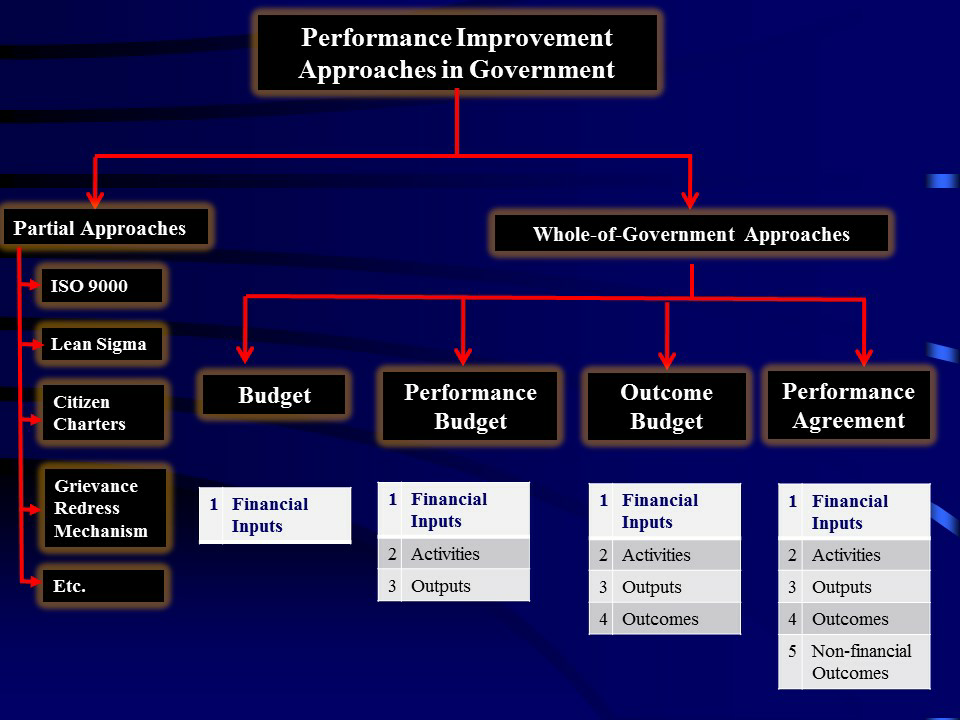

First, as argued in an earlier column, there is a big difference between comprehensive, whole-of-government approaches (budgeting, performance budgeting, outcome-budgeting and performance agreements) and partial approaches to performance improvement (ISO 9000, Lean Sigma, etc.). Partial approaches are akin to arranging chairs on the deck of Titanic. In a dysfunctional system, looking for pockets of excellence is a futile exercise.

Secondly, we need to make a distinction between monitoring and evaluation. Evaluation deals with the final results and monitoring with the activities and processes leading up to the final results. Monitoring and Evaluation are, in fact, complementary and require different techniques and methodologies. Unfortunately, often they are offered as substitutes.

Finally, this is really a false choice. Those offering these approaches as options, overlook the fact that management technology too evolves like any other technology, such as the all familiar information and communications technology (ICT). Today, most of us use the fourth generation (4G) internet connectivity for our fifth-generation smart phones. The choice among various options for performance improvement mentioned earlier is like a choice between a flip phone and a smart phone. That is, there is really no choice. Unless, of course, you also prefer a vintage car to go to work every day.

The following figure summarizes some of the main whole-of-government approaches to performance improvement, all of them are predicated on the belief that what gets measured, gets improved. Also, to know whether the management efforts are yielding any results, one must have a way to evaluate results of these efforts.

These approaches fall under the genre of Management by Objectives (MBO). The technology of measuring and quantifying objectives in MBO has taken a quantum leap. Indeed, there was time when everyone believed that what government did could not be evaluated. That is, they believed the outputs in government could not, and perhaps, should not, be evaluated. Thus, the focus was on “inputs” and “due process.” In this context, budget was considered an effective tool for controlling financial inputs and, through financial control, all other inputs. Thus, budgets became the primary tool for performance management and spending within budgetary limits was considered “good” performance.

As a result of the dissatisfaction with the narrow focus of budgets on inputs, the 60’s and 70’s saw the widespread advocacy and adoption of “performance budgets.” In addition to financial information, they included information on activities and outputs associated with government departments. This new version of MBO improved the way objectives were defined and measured.

Soon there was a realization among policy makers that “performance budgets” were missing perhaps the most important aspect of government performance – the final outcomes for the society. Thus, came the wave of “outcome budgets” in governments around the world in the 80’s and 90’s. Unfortunately, most governments simply, and somewhat mechanically, specified outcomes for various items of departmental expenditure. Thus, we saw examples of ridiculous outcome budgets specifying outcomes for each line item in a budget or simply mentioning outcomes as another table, without any organic links.

Even outcome budgets structured more thoughtfully were found to be ineffective for government performance management. Primarily, because outcomes are a long-term concept. However, most governments operate on an annual cycle. Therefore, how does one evaluate the performance of an officer in the government each year when it takes several years for the outcome to materialize? By the time expected outcomes materialize, the officers have been moved around. This is the primary reason why outcome budgeting never worked in any country and has been pretty much abandoned by all.

In addition, “outcome budgets” were primarily focused on the outcomes related to budgetary expenditures. However, as we know, there are a large number of things we do in government that do not require any financial outlay. Indeed, many innovations could actually save money.

In response to prevailing dissatisfaction with the state of management technology in the government, New Zealand pioneered a revolutionary approach to government performance management in the late 80s. Inspired by techniques used in the private sector and the army, it has come to be known as the New Public Management (NPM) and, explicitly or implicitly, it dominates everyone’s thinking in public administration.

Performance Agreements are the centerpiece of NPM. In New Zealand, for example, the Public Finance Act of 1989 provided for a performance agreement to be signed between the head of a government department and the concerned minister every year. They got a worldwide boost when they were made part of the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) of 1993 by the US Congress. The performance agreements typically describe the key result areas that require the personal attention of the departmental head. The expected results in a Performance Agreement cover all relevant aspects of departmental performance – static dynamic, financial, non-financial, quantitative and qualitative. These are prioritized and expressed in verifiable terms. The performance of departmental head is assessed every year with reference to the performance agreement.

Today, Performance Agreements, the latest incarnation of the MBO approach, are used widely in both the developed and developing worlds and they have overcome many of the fatal flaws of previous approaches. While not yet perfect, technically, they represent a far superior option compared to others. Performance Agreements in fact represent the fourth generation MBO technology in the government and they should be the starting point for all serious efforts to improve performance of government departments. Other options do not represent a viable choice and policy makers should be careful not re-invent the wheel.

This blog first appeared on the American Society for Public Administration's website and is reposted with permission.