Predictive Analytics: How to Prevent Crime from Happening

City police departments across the country are turning traditional police officers into “data detectives.” Police departments across the country have adapted business techniques -- initially developed by retailers, such as Netflix and WalMart, to predict consumer behavior -- to predict criminal behavior. A new IBM Center report, by Dr. Jennifer Bachner at Johns Hopkins University, tells compelling stories of the experiences three cities -- Santa Cruz, CA; Baltimore County, MD; and Richmond, VA – are having in using predictive policing as a new and effective tool to combat crime.

Predictive Analytics Reach Beyond Policing. While this report focuses on the use of predictive techniques and tools for preventing crime in local communities, these techniques and tools are being applied to other policy arenas, as well, such as the efforts by the Department of Housing and Urban Development to predict and prevent homelessness, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s efforts to identify and mitigate communities vulnerable to natural disasters.

Dr. Bachner says that predictive analytics – in policing or other policy areas – is not a silver bullet. It is an additional tool that supplements existing methods. For example, community policing – where officers build trust and neighborhood-level relations -- is an important strategy for deterring crime. “Nevertheless,” she notes, “policing, like many other fields, is undoubtedly moving in a data-driven direction.”

Santa Cruz, CA, Is a Pioneer. The Santa Cruz, California Police Department (SCPD) was one of the first in the U.S. to embed predictive policing in its regular, day-to-day operations. A pilot began in mid-2011 and expanded to the entire city by mid-2012. In the pilot phase, burglaries dropped by 27 percent when compared to the previous year.

What did they do? According to Bachner:

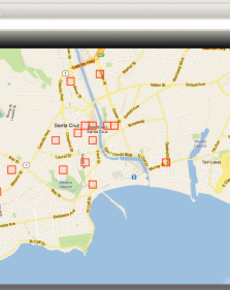

“The core of the SCPD program is the continuous identification of areas that are expected to experience increased levels of crime in a specified time-frame. A computer algorithm draws upon a database of past criminal incidents to assign probabilities of crime occurring to 150 by 150 meter square cells on a map of Santa Cruz. The database includes the time, location and type of each crime committed.

In the calculations of probabilities, more recent crimes are given greater weight. The program then generates a map that highlights the 15 cells with the highest probabilities. Prior to their shifts, officers are briefed on the locations of these 15 cells and encouraged to devote extra time to monitoring these areas. During their shifts, officers can log into the web-based system to obtain updated, real-time, hot-spot maps.”

In an article in the local paper, Santa Cruz Deputy Police Chief Steve Clark said: "It's almost like Neighborhood Watch in the next century."

But having the technology doesn’t mean it will get used, notes Dr. Bachner. Analytic techniques such as hierarchical and partitioned clusters can be intimidating to non-analysts. She found that getting buy-in by the on-the-street police officer was crucial. Otherwise, the data would not be used. She says “there cannot be top-down implementation; it cannot be imposed on unwilling officers as a replacement for experience and intuition.” She says that once officers began using it to supplement their traditional approaches, they liked the positive results. She also said that with staff cuts of 20 percent in recent years as a result of budget constraints, that the new approach made the force more efficient.

Lessons Learned. Dr. Bachner’s observations of the adoption of predictive policing by Santa Cruz and other communities led to several insights. These insights probably hold true in other policy arenas, as well:

- First, just get started. It is a cost-effective way to “do more with less.” Initial start up costs are typically recovered quickly.

- Second, predictive policing should be treated as an addition to, not a substitute for, traditional policing methods. She says top-down implementation is often unsuccessful: “officers were most likely to incorporate predictive methods into their decision-making when they were motivated to do so by their peers rather than their supervisors.”

- Third, make the software available to frontline officers. One of the biggest advantages is access to real-time information, such as maps, which needs to be accessible while in their cars or foot patrol.

- And finally, designate “champions” committed to the use of analytics as a way of doing business. In Richmond, VA, this was its crimes analysis unit. This unit split analysts’ time between analysis and serving in an assigned precinct. As a result, they were able to communicate readily with other officers and provide on-the-job training on analytic techniques.

Graphic Credit: Courtesy of Santa Cruz Police Department