An Opportunity of a Lifetime : Unexpected Monies to Address Long-Standing Needs

States and localities-imposed austerity measures in the early months of the pandemic as sales tax revenues plunged and they faced unprecedented unemployment claims. Their spending dropped 6 percent on an annual basis in the second quarter of 2020. This was the biggest decline in nearly seventy years, and it continued to drop. Florida, for example, projected a $2.7 billion budget deficit at the end of 2020.

In March 2020, Congress provided states and localities $150 billion in stopgap funding to battle the coronavirus as part of the larger $2.2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act). These funds were targeted to mitigating costs of the public health emergency created by the pandemic and had to be spent by the end of 2021. But states and localities continued to predict dire financial circumstances. By the end of the year, they had hemorrhaged 1.3 million jobs, mostly in education.

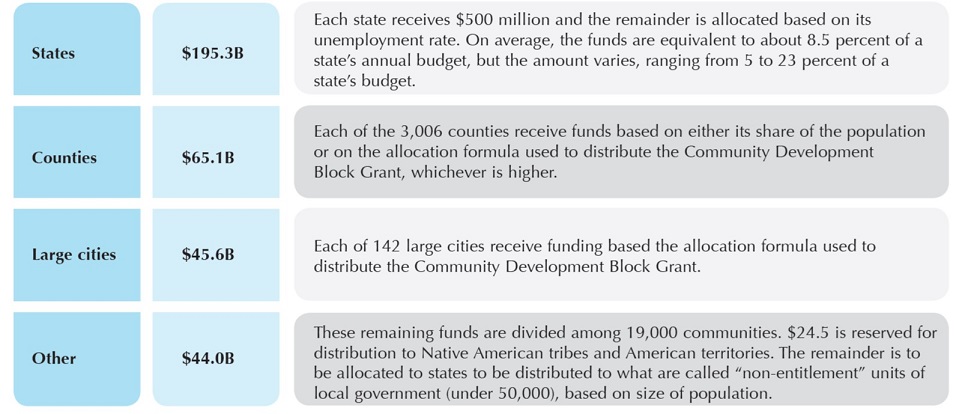

In March 2021, as part of the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, Congress provided a second fiscal infusion of $350 billion to states and localities via a new program—the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund. This program provides states and more than 19,000 localities the greatest fiscal flexibility since the General Revenue Sharing program in the 1970s. These new monies are equivalent to 5 to 23 percent of a state’s annual budget, depending on the distribution formula, and averages nationally about 8.5 percent. For many localities, the funds are equivalent to 25 to 50 percent of their annual budgets, according to the Brookings Institution.

According to the U.S. Treasury, which administers this program, this historic windfall is intended to “help turn the tide on the pandemic, address its economic fallout, and lay the foundation for a strong and equitable recovery.” There is substantial flexibility in how these funds can be used—a flexibility unseen in federal grants since the 1970s.

What is the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund?

The Recovery Fund’s main purpose, according to one of its architects, Gene Sperling, who is now the overall White House coordinator for the implementation of the broader American Rescue Plan, is based on a lesson learned in the 2009 Great Recession: that a broad economic recovery isn’t possible without fiscally healthy state and local governments. The main purpose is to allow them to avoid painful budget cuts and layoffs.

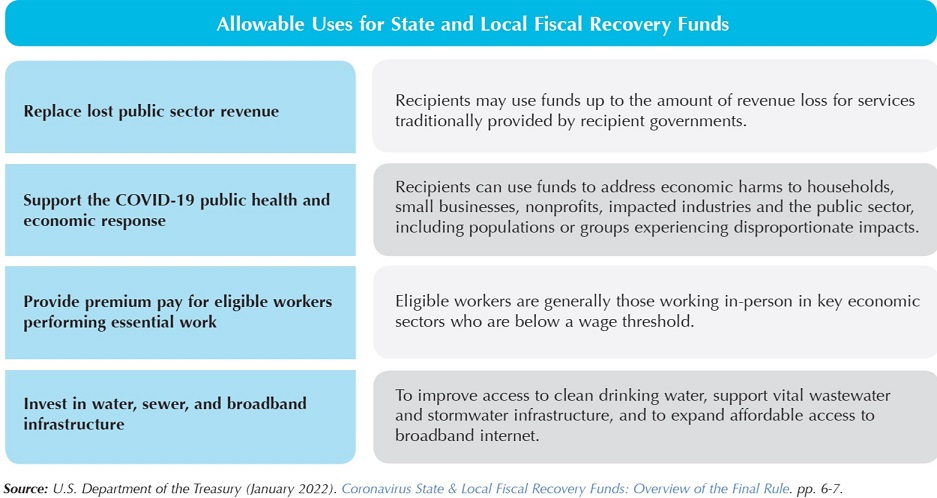

Recovery Fund monies can be used for more than just revenue replacement or to mitigate the impact on local economies and individuals (such as rent relief or pay boosts for essential employees). States and localities can also use the funds to provide services to communities disproportionately affected by COVID-19, to expand access to broadband, and for other longer-term investments such as water and sewer infrastructure. The program’s chief goal is to lay a foundation for a systemic, strong, and equitable recovery.

While the potential uses of the Recovery Fund are broad, there are several specific restrictions—the monies cannot be used to replenish under-funded pension funds, or “rainy day” funds, or to cut taxes. Interestingly, Treasury’s guidance on allowable uses specifically encourages building state and local capacities to develop and use evidence and data to better manage their overall performance. The guidance notes: “State, local, and tribal governments may use payments from the Fiscal Recovery Funds to improve efficacy of programs addressing negative economic impacts, including through use of data analysis, targeted consumer outreach, improvements to data or technology infrastructure, and impact evaluations.” In addition to flexible uses of various pandemic relief funds, the monies are distributed more broadly than any grant program since the General Revenue Sharing program of the 1970s:

For the most part, half of these monies were distributed to recipients in May 2021. Most of the remainder will be distributed in May 2022.1 These funds must be spent by the end of 2026—another lesson from the 2009 Recovery Act: unnecessarily short spending deadlines can result in projects that do not address longer term community needs.

Treasury Guidance on Uses and Reporting

How can we ensure this large infusion of funds is used wisely and in the spirit of the law? In April 2021, the Office of Recovery Programs was created and tasked with quickly designing the distribution, use, and accountability for this program. By law, the initial funds had to be distributed within 60 days after the law was signed. The first tranche of grant monies was distributed in May 2021 before official, final program guidance had been developed. This caused great uncertainty among state and local recipients—they feared spending the funds on new initiatives and then see these funds “clawed back” later when final guidance was issued and they find their initiatives were deemed as not being “allowable costs.” As a result, states and localities were initially slow to spend the funds.

Treasury staff quickly scrambled to develop interim guidance before the funds were distributed in May 2021. When the final version took effect April 1, 2022, Treasury noted that this guidance “provides state and local governments with increased flexibility to pursue a wider range of uses, as well as greater simplicity so governments can focus on responding to the crisis in their communities and maximizing the impact of their funds.”

The guidance creates different tiers of reporting and frequency of reporting. Recipients with more than 250,000 population have to submit “an annual Recovery Plan Performance report which will provide the public and Treasury information on the projects that recipients are undertaking with program funding and how they are planning to ensure project outcomes are achieved in an effective, efficient, and equitable manner.”

These large recipients, as well as other recipients of awards over $50,000, are required to submit quarterly project and expenditure reports through the end of the program in 2026. Treasury created an electronic “submission portal” and templates to simplify reporting. The guidance encourages reporting the “amount of project funds allocated to evidence- based interventions.” Smaller recipients (less than $5 million) do not have to submit plans or quarterly reports, but must submit annual reports on spending, including contracts or grants over $50,000, as well as descriptions of the types of projects funded.

According to RouteFifty, an online magazine covering states and localities, some small localities are foregoing the aid. “Generally they just don’t have the infrastructure to support the reporting requirements required under the law,” said Emily Brock, director for the Government Finance Officers Association. These include communities of 500 or less where most of the work is done by community volunteers unfamiliar with complex programs.

However, the value of these reporting requirements, especially by larger jurisdictions, will be to fill a blank space that existed after massive spending in 2009 under the Recovery Act: did the monies make a difference? The Recovery Act required detailed reports on spending, but not on whether the monies spent led to improvements. The Biden administration is encouraging recipients to use funding to stabilize their immediate need to support existing services but also to invest in longer-term recovery programs, in a sustainable and equitable manner. The reporting requirements for the Recovery Fund, according to an article in Government Executive, are envisioned to fill that blank space this time around.

Spending Advice from Experts

States and localities were initially unsure as to how they might handle this massive cash flow, especially since the original projections of large-scale revenue shortfalls from their own tax sources proved to be wrong and many had unexpected surpluses. The Urban Institute reported that tax revenues grew 17.3 percent in August 2021, compared to a year earlier. RouteFifty reported that some state lawmakers see this as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to invest in long ignored community needs “thanks to booming tax revenues and federal aid.” An early study by the Brookings Institution of spending plans developed by large cities recommends they use some of these funds to develop comprehensive strategies to reverse decades of decline as a result of budget cuts over the years.

Bill Leighty, a longtime advisor to states and localities, sees them “awash in money” thanks to the federal Recovery Fund and they are “struggling with how to spend it.” His home state of Virginia received $4.3 billion and its localities have been allocated $2.9 billion on top of that amount. The City of Richmond’s allocation, for example, is equivalent to 20 percent of its annual budget. So how should they approach spending wisely?

Leighty observes that most communities have created working groups to create consensus on priorities for spending. Many also have appointed an accountability officer to track spending. He recommends uses that will not create a long-term stress on budgets after the federal monies run out in 2026. For example, he recommends using funds to tackle deferred maintenance and invest in parks, recreation, and affordable housing—and not to hire more staff, since such positions would either have to be terminated or funded with local resources after the federal aid runs out.

Who Makes Decisions on How Funds Are Used?

At the state level, tensions arose over whether the governor or the legislature would have the authority to determine spending priorities over their portion of the grant monies. As RouteFifty notes, “You might think this would be the kind of question for which there would be a simple, standard answer.” But no. In fourty states, the governor has authority to spend unanticipated federal funds without legislative approval, with some restrictions. The tensions are even starker in those states where the legislature is controlled by a different party than the governor, such as North Carolina.

At the local level, there is large variation in the extent to which city councils proactively seek citizen input as to spending priorities. RouteFifty writes that Alexandria, Virginia, which will receive about $60 million, is surveying residents for their input, using a range of approaches beyond traditional public hearings. In Charleston, West Virginia, community input in minority neighborhoods may lead to the expansion of a local food co-op and allowing food stamps to be used in local farmers markets to purchase produce.

Baltimore is a good example of how large cities are managing historic funding amounts. These monies total $641 million—$141 million allocated to offset budget cuts, the remaining $500 million to fund recovery programs. By the end of 2021, Mayor Brandon Scott’s organized proposals for spending around five priority “pillars,” such as equitable neighborhood development and clean and healthy communities. About one-third of more than 500 proposals came from city agencies; the remaining two-thirds from nonprofits. For example, the city health department proposed increasing vaccination rates by operating mobile clinics. The proposals then were integrated into the city council’s approval process.

Where Are Funds Being Invested?

Treasury encourages states and localities to invest in “evidence-based” interventions where possible. However, Brookings saw few “transformational” investments in the early plans submitted to Treasury that would emphasize long-term support and build systems capacity.

At the state level, the National Association of State Budget Officers reviewed thirty-nine state plans publicly available as of October 2021. It found that these states had defined allocations for only about half their funds (as of August 2021): 32 percent to replace lost revenues, 16 percent to infrastructure, and 9 percent for public health priorities.

An October 2021 survey by the National League of Cities found that two-thirds of cities “expect to use American Rescue Plan Act money to cover lost revenues.” It concluded that these funds helped localities to avoid painful choices, such as further layoffs of employees and cutting essential services. The second-most cited use of Recovery Funds was to ameliorate the negative economic effects of the pandemic to small businesses, households, and nonprofits.

Results for America, an advocacy and research nonprofit for more evidence-based government, reviewed 149 initial plans by large cities and counties that were submitted in August 2021 to Treasury. It found that about half were investing in ways to engage their communities more meaningfully to determine funding priorities. For example, Cook County, Illinois, hosted meetings and conducted surveys with community-based organizations in historically marginalized communities, and created a process for ongoing engagement.

Localities with preexisting programs and priorities were able to move more quickly. For example, Detroit’s workforce development initiative is using its funds to expand a preexisting “Skills for Life” pilot initiative to help individuals get ready for work. This program, run as a pilot for five years, was found to reduce poverty by 90 percent. Similarly, King County, Washington, had a preexisting Social Justice Strategic Plan that prioritizes homelessness as well as community health and equity. The goal is to report not just dollars spent but the results—whether people are better off and who is better off.

Conclusion

The bottom line, according to several experts, is that the fear that the massive influx of federal aid would be wasted or would primarily be used to balance budgets or cut taxes seems to be unfounded. For example, public finance expert Girard Miller, writing in Governing magazine, calls the State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund an “unintended social science laboratory.” He wrote, “It’s going to be important for the state and local government community to be able to show politicians, pundits and voters that the federal money they received is mostly being well and wisely spent,” and that serious studies of “outcomes” of these diverse experiments can show the funds benefited their most needy residents. As the quarterly spending reports become available over the course of this year, they will be a rich resource for researchers to make such assessments, and for states and localities to demonstrate that they can make a difference.