Government Reform over the Past 20 Years - Part 2, Managing Performance

In the IBM Center’s new book, Government For The Future: Reflection and Vision for Tomorrow’ Leaders, we have identified six major trends that have driven government management reforms. This is the second in a six-part series where we highlight each trend; part two summarizes the evolution of performance management in U.S. federal, state, and local governments. For more detail, see the chapter on Managing Performance.

Performance information has long been collected and used to varying degrees at the federal, state, and local levels in the U.S. since the early 1900s, as part of the reforms brought about by the Progressive Movement. Localities and several state governments began developing performance measurement systems more methodically in the 1970s. The federal government undertook some performance-related initiatives, such the Defense Department’s Planning, Programming, and Budgeting System (PPBS) of the 1960s, but other agencies did not begin in earnest until the passage of the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 (GPRA). That law required federal departments and agencies to develop strategic plans, annual performance plans, performance measures, and annual performance reports.

By 2010, a number of lessons had been learned in the course of implementing GPRA in how to effectively develop, use, and govern a performance management system. Many of these lessons came from the Government Accountability Office’s (GAO’s) observations in various reports on GPRA’s implementation, but also from agencies’ practical experiences with the effectiveness and impact of various performance management routines. Changes based on these lessons were incorporated into the GPRA Modernization Act of 2010.

In addition to federal performance-related efforts, a number of state governments adopted laws similar to GPRA. In addition, professional communities (such as those involved with the implementation of foster care programs) and municipal professional associations developed standard measures for common functions, such as waste collection and emergency response. Likewise, by the 2010s, a number of nonprofits, foundations, and advocacy groups supported initiatives related to improved performance, evidence, and analysis.

Background: The Arc of Performance Management

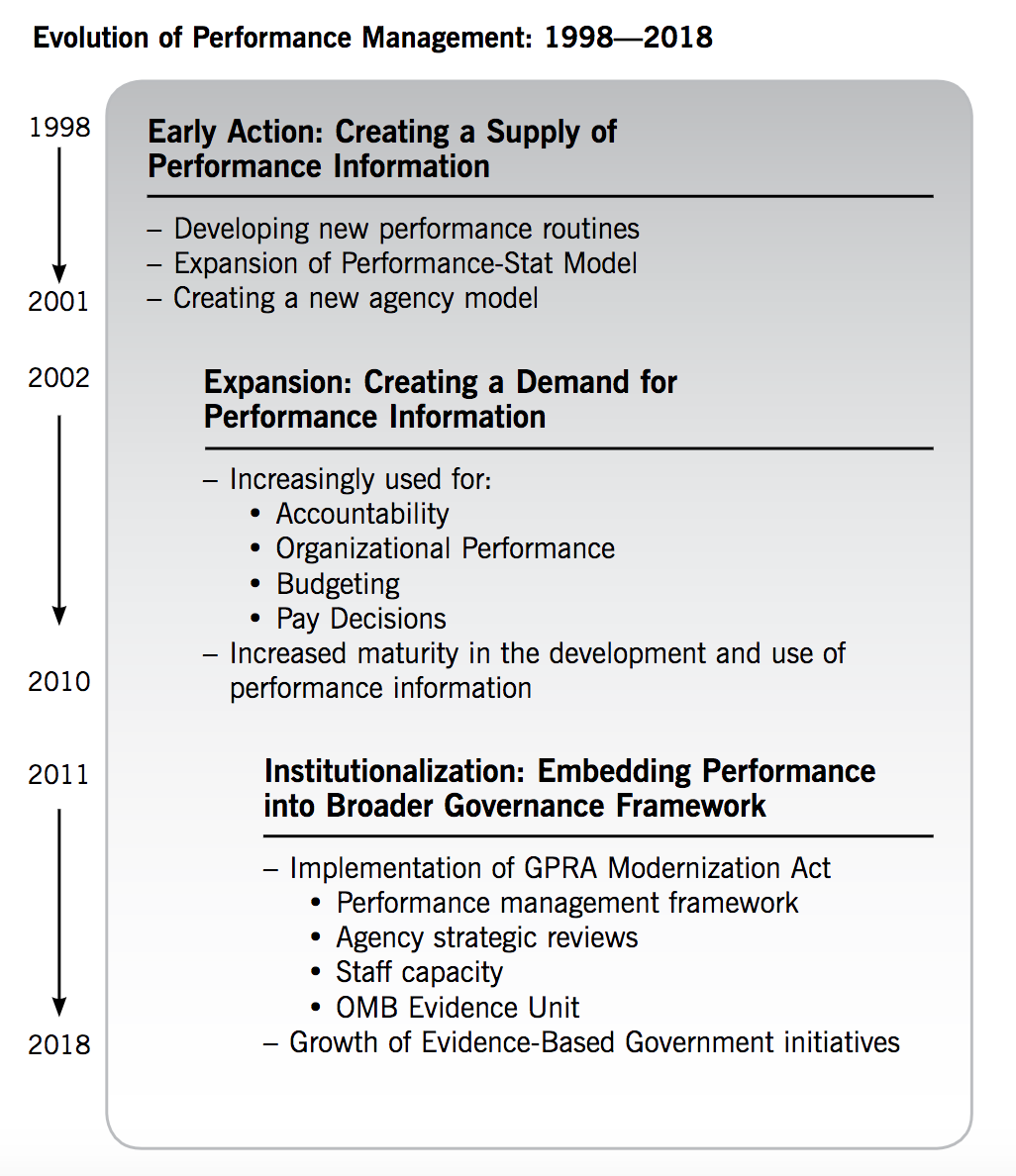

Progress in this arena has moved through three major phases over the past 20 years.

- Early action: In response to the adoption of the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993, federal agencies began developing performance management routines to create a supply of performance information. This started with the development of agency strategic plans, annual operating plans, performance measures, data collection systems, and data reporting systems. In addition, there was a new focus by agency leaders on achieving program “outcomes” instead of “outputs.” While agencies made a limited use of performance information to manage at the federal level, there were pioneering efforts to do so at the local level.

- Expansion: This phase reflected the beginning in the shift from creating a supply of performance information, to creating a demand for its use by managers and policy decision makers. This included uses such as for accountability, operational management, and to inform budget and pay decisions. This phase can also be characterized as the beginning of the development of more sophisticated approaches to collecting and using information, such as measures of “unobserved events” (e.g., illegal drug smuggling) and predictive measures, such as where and when crimes are more likely to occur.

- Institutionalization: Lessons learned from more than a decade of experimentation and observation were incorporated into an update of the GPRA law in 2010. This included newly defined governance structures, a more stable operating framework, and new authority for agencies to work collaboratively on shared outcomes. In parallel, technological advances made data collection and reporting less burdensome and more available for analysts and decision makers. This contributed to new demands for evidence-based decisions and new performance-based program models, such as tiered evidence grants and Pay-for-Success programs.

Lessons Learned and Looking Forward

Because of the statutory framework and a bipartisan commitment by top government executives, the performance movement seems assured of a place at the table in coming years. Yet, still more needs to be done before performance becomes embedded as part of the government’s culture. Following are several lessons gleaned from observations over the past two decades:

- First, it takes time, effort, and commitment.The seemingly simple goal of “creating performance information that is useful and used” sounds easy, but in reality there are substantial challenges, both technical and personal, to meeting that goal.

- Second, successfully linking performance information to decisions is less a technical issue than a human behavioral issue. Both managers and employees must trust data before they will use it for actions that may have significant consequences.

- Third, performance information is increasingly used by a broader set of government and public users. While congressional use lags, performance information is increasingly used by government executives and program managers to inform operational decisions and budget choices.

While performance management may now be formally institutionalized via the GPRA Modernization of 2010, it still is not ingrained as part of the organizational culture in government. Going forward, three key steps could help further ingrain the use of performance management approaches to create a culture where decisions are based on data and evidence, including:

- Embedding performance management as a part of the front-lineculture: Line managers need to view performance management not as a compliance cost but a way of doing business.

- Creating stronger, more explicit “line-of-sight” links: Creating links between broader strategies, program budgets, and individuals will improve decision making and demonstrate relevance.

- Making performance information more granular, real-time, contextual, predictive, and intuitive: Managers are more likely to use information that is relevant and reliable for their specific needs, and tied to how they normally “do business,” whether through administrative systems or their agency’s budget process.