An Agile “Tipping Point” for Governments?

In the United States, trust in government at all levels and in all branches is at extremely low levels. Almost two-thirds of those polled by Gallup in January 2019 indicated that they had little or no trust in the federal government’s ability to handle domestic problems. In similar domestic Gallup surveys, state and local governments fared little better, and global Gallup results show that declining trust in government is an international phenomenon.

Certainly, political conditions contribute to this mistrust, but failure to deliver consistently on key issues that the public cares about and continued perception of inefficiency—waste, fraud, and abuse—also fuel the negativity.

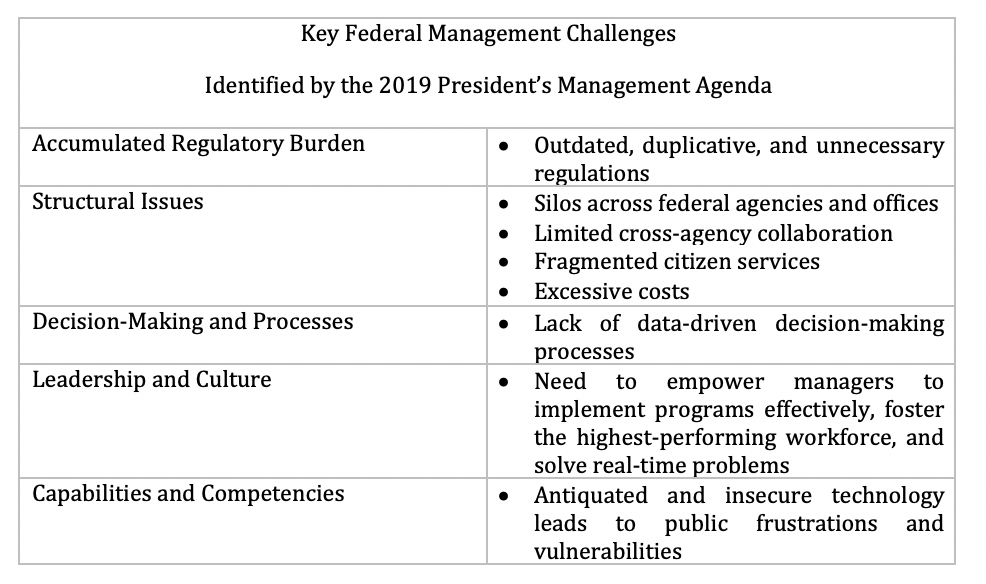

The 2019 President’s Management Agenda identified five major problems at the federal level, outlined below. Similar problems exist at the state and local levels and in other countries.

How can the public sector solve these problems? In dealing with unhappy customers and falling profits, the private sector has increasingly turned to management methods based on agile principles used in software development. In the The Age of Agile, author Stephen Denning calls the shift to agile management principles, “[a]n unstoppable revolution . . . conducted in plain sight by some of our largest and most respected corporations.”

Let’s look at what Agile Principles are and how they are being applied in corporations, the military and public policy. Further, let’s explore what next steps might be taken to bring agile management techniques to governments around the world.

What is Agile?

In software development, agile features small, cross-functional, self-organizing teams that include customers working quickly to deliver solutions in increments that immediately provide value. The development is customer-centric, and networks are used for development and deployment.

What are Agile Principles?

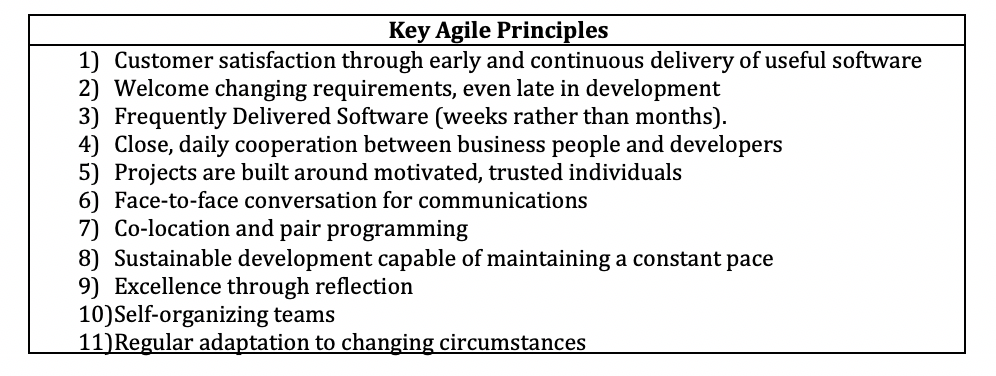

The Agile Manifesto was developed in 2001 by a group of software developers who grew frustrated by the paradigm governing their industries. The Manifesto’s principles outlined below continue to guide projects and programs of software development today. Agile developers use “scrums” and “sprints” as techniques to produce products quickly that have a high degree of customer acceptance and satisfaction. However, these principles can be adapted to management.

Application of Agile Principles

Denning gives us three “Laws” for the application of agile management principles:

- The Law of Small Teams. “In a VUCA (Violent, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous) world, big and difficult problems need to be disaggregated into small batches and performed by small cross functional autonomous teams, working in relatively short cycles in a state of flow, with fast feedback from customers.”

- The Law of the Customer. “The epic shift in power in the marketplace from seller to buyer (creates) a need for firms to radically accelerate their ability to make decisions and change directions in light of unexpected events.”

- The Law of the Network. This is the “lynch pin.” Denning suggests that a vertical hierarchy is no match for an interactive network.

Other scholars offer support for this view. Anne-Marie Slaughter brings networks to the public realm in her book, The Chessboard and the Web: Strategies of Connection in a Networked World. Just as Denning contrasts vertical bureaucracies with agile organizations, Slaughter contrasts the chessboard—the traditional approach to diplomacy—with the web. The network mindset, she contends, is able “to convert three dimensional human relationships into two dimensional maps of connections, and to see the relationships between people and institutions.”

U.S. Army General Stanley McChrystal reinforces those points in recounting his leadership of the Joint Special Operations Forces that confronted al Qaeda in Iraq and later the Taliban in Afganistan in his book, Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. McChrystal knew that al Qaeda operated as a series of networks, and he was determined to change his own organization from a heirarchy to a network. McChrystal created small groups with divergent skills, each bound together by trust and a shared sense of purpose, that acted as a “seamless unit” exercising joint cognition in changing circumstances.

While neither Slaughter nor McChrystal used the term “agile” to describe their prescriptions for success, they are very consistent with Denning’s findings and my own expericence in implementing the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 during the financial crisis. Our mission was clear—save the economy from further collapse—with the President and Vice President providing the top cover for our eight-person Recovery Improvement Office. We were able to catalyze a set of interconnected networks to rapidly meet the objectives of the Act, distributing more than $800 billion in a very short period of time with virtually no allegations of waste, fraud or abuse.

How do we take these lessons learned and apply them to helping governments around the world become more agile?

Toward Agile Government

It is critical that we develop a reform agenda to make governments at all levels more agile. For example, we should work to identify key Agile Government principles; identify instances of agile government around the country and around the world in order to develop “best practices” that can be available to governments and researchers; and collaborate with governments that wish to use agile principles in their projects, programs, and overall organizational design to assist with strategy and implementation. We plan to work with the National Academy of Public Administration and other key stakeholder groups as partners in this initiative.

Conclusion

In his book, Tides of Reform: Making Government Work, author Paul C. Light identified reform efforts from 1945 to 1995 that sought to improve how government operated. I believe that Agile Government can be a new tide that lifts governmental ships around the world. Success will require a new mindset in government and new organizational models. Not every activity of government may adopt agile principles. However, the same “Unstoppable Revolution” that Denning describes can help drive progress toward building efficiency, effectiveness, and trust in the public sector.

Mr. DeSeve, a former senior official with the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, is a Visiting Fellow at the IBM Center for the Business of Government and a Fellow of the National Academy of Public Administration.